Background information

No longer glamour, but dust: "Mafia 4" and the harsh everyday life of Sicily around 1900

by Kim Muntinga

Telegraphy was already being used to transmit messages and images over 150 years ago, and photo and wireless transmission followed at the beginning of the 20th century. Global data networking isn’t all that new.

The world didn’t just become connected with the Internet. Before that, there was the telephone network – which could also be used for data transmission, via fax machines, for example. But the telephone network wasn’t the first global communications network. A global network had already been built in the 19th century – the telegraph network.

Telegraphy changed the world in a similar way to the Internet. Before telegraphy, there was no way to transmit messages quickly over long distances, so people relied on the post. An undersea cable being laid across the Atlantic drastically reduced the transmission time for messages from several weeks to a few hours. From the very beginning, telegraphy was very important for journalism, as well as for political and economic decision-making.

When I say telegraphy in this article, I always mean electrical telegraphy. Humans have long used other forms of telegraphy: messages can be transmitted using coded light signals or acoustically using drums, but their range is limited in comparison.

Telegraphy’s based on the movement of electricity along a wire. At one end of the wire is an input device, and at the other, a receiving device. In its original form, the input device is extremely simple: it’s just a button. Pressing it closes the circuit and sends current through the wire. When the button’s released, it breaks the circuit.

Similar to tapping, the sequence of signals and pauses can create a code, allowing information to be transmitted. Morse code has become the established standard for this, consisting of short signals – recorded as dots – long signals – recorded as dashes – and pauses. In the Morse alphabet, letters, numbers and special characters can be encoded into electrical signals and then decoded.

..-. ..- -. / ..-. .- -.-. - ---... / -.. . .-. / -- --- .-. ... . -.-. --- -.. . / ... - .- -- -- - / .. -. / ... . .. -. . .-. / .... . ..- - .. --. . -. / ..-. --- .-. -- / --. .- .-. / -. .. -.-. .... - / ...- --- -. / ... .- -- ..- . .-.. / -- --- .-. ... . .-.-.- / -.. . .-. / . .-. ..-. .. -. -.. . .-. / -.. . ... / ... -.-. .... .-. . .. -... - . .-.. . --. .-. .- ..-. . -. / .-.. . .. ... - . - . / .- -... . .-. / -.. .. . / ...- --- .-. .- .-. -... . .. - .-.-.-

At the other end of the line is a pen that records these signals as deflections on a moving strip of paper – a writing telegraph. Later, these signals could also be converted into a beep. This was easier for a skilled telegraph operator, as they were able to translate the Morse code as they heard it and write down the message.

The physical principles of electrical telegraphy were already known to scientists in the early 19th century. Numerous inventors experimented with electrical signal transmission, but there was no standardised method, and the practical benefits weren’t yet clear. Lines were short too. A line in Göttingen between the workplaces of mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss and physicist Wilhelm Eduard Weber was one kilometre long. That was considerable back then.

American Samuel Morse introduced his first telegraph to the public in 1837. At that time, it used a much more complex coding system than the Morse code that would later become commonplace. This was developed in the following years by his colleague Alfred Vail. The technology was also improved in other ways. Morse tried for a long time – unsuccessfully – to obtain government or private funding to build the infrastructure. In 1844, the first long telegraph line finally began operating in the USA, between Washington and Baltimore.

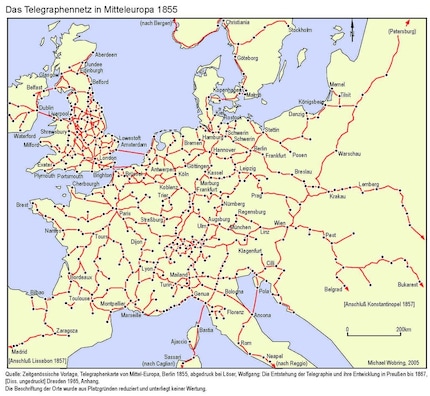

Telegraph lines already existed in Europe – especially in England, where rail expansion and telegraphy went hand in hand. However, it wasn’t until the second half of the 19th century extending the network really gained momentum. Switzerland began building a telegraph network in 1852 – somewhat later than its neighbouring countries, but more thoroughly. By the end of that year, 34 stations were in operation. The map below – showing the situation in 1855 – outlines the comparatively dense telegraph network Switzerland had at that time.

The lines were often laid along railway lines. This also allowed information about the trains to be transmitted. For a time, the railway was a safe method of escape for robbers, as nothing was faster than a moving train. Telegrams changed that. Staff at train stations were informed about the criminals and lay in wait with handcuffs.

Underwater cables presented a particular challenge. In 1850, the first submarine cable was laid between France and England. Despite the short distance, it only lasted a few hours due to a lack of suitable, durable insulation material.

In 1857, the private Atlantic Telegraph Company began attempting to lay a submarine cable across the Atlantic. The pioneers faced huge difficulties, starting with the fact that the 4,600-kilometre cable couldn’t be loaded onto a single ship. Two ships sailed to the middle of the Atlantic, joined the cable ends, and laid the line in both directions simultaneously. However, the cable broke several times during the laying process. The ships encountered a storm, and the compass malfunctioned, presumably due to the cargo. When the line was finally completed after over a year and three attempts, there was great enthusiasm on both sides of the Atlantic.

Not for very long, though, as this cable also quickly broke. After just a few days, the signals became weaker. The decision was made to counteract this by increasing the voltage to 2,000 volts, which ultimately destroyed the cable. This was followed by an extended break, partly due to the US Civil War. The next attempt wasn’t made until 1865. Which also failed. In 1866, on the fifth attempt, a permanently functioning submarine cable was finally established.

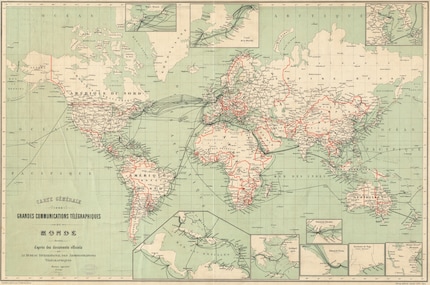

This Atlantic cable definitively proved that a global telegraph network could be built. In 1865, the so-called Turkish line, running from London to India, began operations. That same year, the International Telecommunication Union was founded to coordinate international telegraphy. The organisation still has its headquarters in Geneva. In 1875, three million telegrams were sent in Switzerland – one million of which were international. By the turn of the century, the network was already advanced.

This map from the early 20th century shows how many submarine connections already existed. Even small islands in the middle of the ocean were accessible. There was even a connection across the Pacific from Australia to Vancouver.

However, the network didn’t mean that everywhere in the world could be addressed directly, as the Internet has now made possible. A telegram from Europe to Australia made its way through intermediate stations, where it had to be decrypted and resent. This could take several days. It was nevertheless a milestone for humanity. After all, there were no planes yet, and transmitting messages halfway around the world would’ve taken at least two months without the technology.

Also, only one message could be sent through a line at a time to start with, although multiplexing later made it possible to send a few simultaneously. As a result, many earlier messages reached their destination via detours because the direct route was already in use. Limited capacity and manual forwarding made telegrams very expensive. Ordinary people only used them in urgent or important situations.

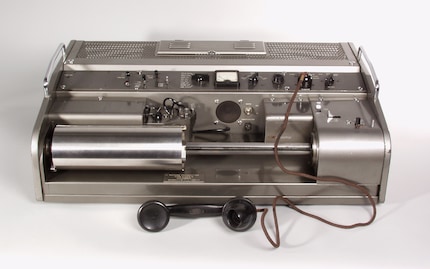

The telegraph network was also used to transmit images. As early as 1855, Italian physicist Giovanni Caselli patented a device he called the pantelegraph. It could transmit simple images up to 10×15 cm in size. It was used primarily in France from 1860 onwards for verifying signatures in banking transactions, among other things.

The images had to be drawn with ink on a zinc foil. Zinc conducts electricity, but ink doesn’t. A machine scanned the foil. If it detected zinc, it sent an electrical signal – if it didn’t, it wouldn’t. This transmitted a negative to the receiver as a result.

Arthur Korn’s invention made it possible to transmit not only drawings but also photographs. Instead of a zinc plate, a standard film strip was used. Using a selenium cell, which changes its resistance depending on the light, a machine scanned the image and converted it into electrical signals. After a few years, the image quality became astonishingly good. This telegraphic photograph of the emperor of Austria, Franz Joseph, dates from 1907. Among other things, the invention was used to transmit photos of wanted individuals.

Édouard Belin also developed a picture telegraph at the beginning of the 20th century. The first successful photographic transmission across the Atlantic was in 1921. The techniques of picture telegraphy were continually developed, with the devices primarily using the telephone network in the 20th century. From 1926 onwards, it was also possible to transmit images wirelessly via radio. Although the so-called Fultograf was a flop, it was also the forerunner of TV and fax.

In 1886, Heinrich Hertz proved the existence of radio waves. This laid the foundation for developing radio broadcasting and radio telegraphy. 1897 marked the first transmission across the open sea near the Bristol Channel over a distance of just under five kilometres. Much greater distances were soon achieved and, in 1901, radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi achieved the first wireless transmission across the Atlantic.

Radiotelegraphy was important for shipping. Previously, ships weren’t able to communicate with the outside world if they were in distress at sea. In 1906, the SOS distress call was introduced. The combination of letters didn’t mean anything specific, but was chosen because it was a very simple Morse code sequence: three dots, three dashes, three dots.

The Titanic, which struck an iceberg and sank in 1912, was able to communicate with other ships via radiotelegraphy. This was the only reason that some passengers survived.

The invention of the telephone was nothing more than an attempt to transmit another form of information over the electrical network. I’m not really surprised that the telephone was invented independently by several people – the idea was obvious. It’s a well-known fact that Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray filed patent applications for the telephone on the same day, 14 February 1876. But similar devices had already been developed by various inventors, starting in 1844 by Innocenzo Manzetti, and from around 1860 by Antonio Meucci and Philipp Reis. The German inventor even called his invention a «telephone».

The telegraph network was the first step toward telephony, but it was only partially suitable for the telephone. Telephony requires higher transmission quality, so the telephone network was initially expanded primarily over short distances at a local level.

The invention of telephony by no means made telegraphy obsolete. For a long time, the two forms of communication existed in parallel. In the first half of the 20th century, even in highly developed countries, only a minority of households were connected to the telephone network. Things changed over the following 50 years. The telegram declined in importance but continued to be used for special occasions. In 1978, the Federal Republic of Germany’s postal service still recorded 13 million telegrams sent.

In Switzerland, the state-owned PTT (Post, Telephone, Telegraph) was split into Swiss Post and Swisscom in 1998. As a result of this split, the telegram service – which had become virtually insignificant – was discontinued in 1999. In Germany, telegrams could still be sent until the end of 2022, but only within the country.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Kim Muntinga

Background information

by Debora Pape

Background information

by Michael Restin