Review

The Running Man: entertainment instead of alarm bells

by Luca Fontana

Netflix documentary The Stringer makes a scandalous accusation: the most famous image from the Vietnam War wasn’t taken by Nick Ut, but by an unknown freelancer. The film leaves out many details, but the core of the story could still be true.

Warning: the following review contains spoilers. It doesn’t just look at the quality of the documentary, but also the content – and the evidence beyond the film. The Stringer has been on Netflix since 28 November.

The Terror of War, more commonly known as Napalm Girl, is one of the most influential images of our time. It shows nine-year-old Kim Phuc running towards the camera, screaming – her back burnt by a mistaken napalm attack intended for North Vietnamese troops. The photo from 1972 is considered a testimony to the brutality of the Vietnam War and its unjust consequences for innocent people. It reached an estimated one billion people within 24 hours.

The picture was taken by Nick Ut, a Vietnamese photographer for the Associated Press (AP). It won him a Pulitzer Prize and the World Press Photo Award. He went on to build a successful career for himself in Los Angeles. Over 50 years later, Netflix documentary The Stringer makes an uncomfortable claim: Nick Ut didn’t photograph Napalm Girl at all.

This serious accusation comes from Carl Robinson. He was one of the AP’s photo editors in Vietnam. Robinson claims his boss Horst Faas ordered him to change the caption. «Make it Nick Ut,» the German is said to have whispered in his ear. The alleged real photographer is a freelancer (stringer) called Nguyen Thanh Nghe. He’s said to have received 20 dollars and a copy as a keepsake.

Make it Staff. Make it Nick Ut.

In 2022, Robinson’s story reaches photojournalist Gary Knight. Together with a team of reporters, he sets out in search of the truth. He interviews eyewitnesses, sifts through footage, commissions a forensic analysis and finally finds the missing freelancer: just like Nick Ut, Nguyen Thanh Nghe also claims to have taken the picture.

This search for clues is thrilling – especially if you’re interested in photography or the Vietnam War. Tragic music, pensive faces and meaningful words drive the film’s narrative forwards. In the end, unbiased viewers will inevitably come to the same conclusion as Gary Knight: The Terror of War was almost certainly not taken by Nick Ut.

For the story to be effective, the documentary paints an unnuanced picture of the protagonists. Nick Ut is a liar. Nguyen Thanh Nghe is a victim who has been deprived of recognition. Carl Robinson is an old man plagued by remorse, and Horst Faas is a ruthless boss with a bad temper.

But wait a minute. What does Horst Faas, himself a titan of war reporting, have to say about the accusations? Or the other photo editor at the time, Yuichi Ishizaki? Or the technician called Huan who was present there? We’ll never find out. Because almost all of them have since passed away. Nick Ut himself refused to be interviewed for the documentary.

This gives The Stringer a very one-sided view of the situation. Whistleblower Carl Robinson is hardly ever critically examined. But his motives are more than questionable. His grudge against Nick Ut and AP is well known and well documented, including in his autobiography. Robinson was against the publication of the photo, because he found it distasteful. But he was overruled by Horst Faas and dismissed in 1978. In the film, he says Nick Ut, «should have just been a lot more humble about it».

The fact that Robinson is only going public with the accusation after more than 50 years raises questions the film asks, but doesn’t conclusively answer. The Stringer often tries to take the moral high ground, and drags people through the mud who can no longer defend themselves. Much of what doesn’t support the hypothesis is ignored or glossed over. Instead, emotional anecdotes from Nguyen Thanh Nghe and his family are given a lot of airtime, even though they don’t prove anything. Their sole purpose is to tug on the heartstrings.

In the end, The Stringer goes so far as to claim there were racist motives. It’s alleged in the film that Horst Faas and AP systematically passed off pictures of local freelancers as their own and exploited Vietnamese photographers. Firstly, there’s no evidence for this, and secondly, invoking claims of racism seems to be a bit of a stretch given the fact that Nick Ut himself is Vietnamese. The bottom line is that the filmmakers’ approach seems unfair, unprofessional and emotionally manipulative.

This is a shame and does a disservice to the film’s alleged aim – the search for the truth. The ad hominem arguments and focus on inaccurate testimonies make Gary Knight and his team less credible. Instead, they should’ve concentrated more on hard facts and examined the blind spots. It wouldn’t have made the story any less fascinating.

The Stringer was released on Netflix on 28 November, just short of a year after its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2025. Since then, it’s caused quite a stir in the photography world. Nick Ut continues to vehemently deny the allegations. He claims he shot the photo himself and then took Kim Phuc to hospital. She confirms the photographer’s account. «Nick took the image and he deserves the credit he has received,» she writes in a statement.

The Associated Press commissioned its own investigation in advance of the premiere. It comes to the conclusion that the evidence isn’t sufficient to strip Nick Ut’s credit for the photo. At the same time, it states there are unanswered questions that’ll probably never be resolved. For example, why the picture appears to be from a Pentax camera instead of Nick Ut’s Leica.

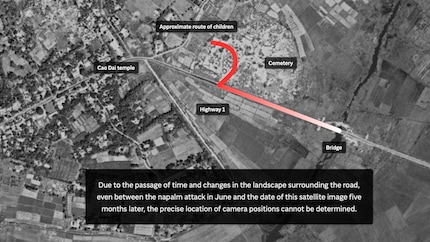

The AP’s report includes its own very readable visual analysis of the footage from the other media outlets present. It’s more sober and fairer than the film. There, a seemingly impossible change of position by Nick Ut is presented as fact. Although the AP also comes to the conclusion that there’s some evidence of this, it points out gaps in the timeline and incorrect calculations in the film.

World Press Photo also investigated this case. Like the AP, the organisation behind the prestigious photography prize concludes there’s reasonable doubt, but no definitive evidence. The organisation considers this doubt to be so great that it suspended the authorship attribution of the image – i.e. credits neither Nick Ut nor Nguyen Thanh Nghe for it. However, the award for the photo still stands.

Nick is the only one who could’ve taken that picture.

Meanwhile, many big names back Nick Ut. Including David Burnett, the photographer seen loading a new film into his camera on the right-hand side in the uncut version of The Terror of War. According to him, Nick was «the one guy who was in a position to shoot the picture». Burnett denies ever saying he was right behind Nick Ut, a statement attributed to him in the documentary.

Although The Stringer uses unfair methods, the core of the story could be true. It’s one person’s word against another. Neither is there any shortage of explanations as to why the other side’s arguments are wrong. Most of the eyewitnesses are either very old or seem biased. The analysis of the facts is more convincing. Here’s an overview of what we know.

What suggests Nick Ut took the photo:

What suggests Nick Ut didn’t take the photo:

Do I personally believe that Nick Ut is deliberately lying? No. He was there that day, and Horst Faas told him he had taken the picture. His talent as a photographer can’t be denied either, as his later career shows. Even if he owes many of his opportunities to this iconic photo and the prizes he won for it.

Do I think Nick Ut photographed The Terror of War? Also no. The evidence to the contrary is overwhelming – even if we disregard the potentially biased eyewitness accounts. Does that justify such a one-sided film that not only questions history, but also accuses many living and dead people of malice? For the third time, no. A high probability isn’t conclusive proof. After more than 50 years, one principle applies here more than ever: innocent until proven guilty.

In the latest podcast episode, we talk about The Stringer from minute 27 onwards:

I would give the subject matter and story of The Stringer five stars. The background to the iconic image is highly charged, and the video footage is impactful, if sometimes hard to watch. And the research led to what’s probably the biggest scandal in the history of photography.

But the film only gets three stars from me. The Stringer displays a lack of neutrality, and ignores some context that doesn’t fit the narrative. It also ruthlessly attacks people on a personal level. Sometimes without evidence. Sometimes without giving people the opportunity to respond, because the accused have passed away. Even the guise of the supposedly unbiased protagonist Gary Knight can’t hide this shortcoming.

If you’re interested in photography or the Vietnam War, The Stringer is essential viewing. My recommendation: watch it – but be sure to scroll through the analysis by the Associated Press afterwards. I’m interested in finding out what you think in the comments.

My fingerprint often changes so drastically that my MacBook doesn't recognise it anymore. The reason? If I'm not clinging to a monitor or camera, I'm probably clinging to a rockface by the tips of my fingers.

Which films, shows, books, games or board games are genuinely great? Recommendations from our personal experience.

Show all