How are games actually made? Vienna-based games manufacturer Piatnik gives us a play-by-play

18/8/2022

Translation: Katherine Martin

Piatnik has been dedicated to game-based fun since 1824. A look behind the scenes at the Vienna-based card and board game manufacturer reveals two hundred years of company history. But can analogue game ideas still hold their own in the digital age?

To heck with smartphones, PCs and consoles. Piatnik has been playing the good old-fashioned way for almost 200 years – and this despite seismic global changes. Industrialisation, wars, economic crises, five different currencies, the fall of the Berlin Wall and, last but not least, digitalisation; Austria’s most famous game manufacturer, Piatnik, has survived it all. «We’ve been lucky. I mean, a bit of luck is essential when you think about everything that’s gone on in the last 200 years. Bombs could’ve fallen on the building at some point,» says Dieter Strehl. He’s the man at the helm of the tradition-steeped company, currently in its fifth generation.

He describes what his family has built over the last two centuries as the «great achievement of previous generations.» He’s been working for 38 years at the company, though this wasn’t always a given: «During my studies, I worked the assembly line at Mercedes. After that, I worked in a bank. It wasn’t until later that I decided that a game manufacturer like this with its sizable list of export contacts would actually be really interesting.»

From card painting to game manufacturing

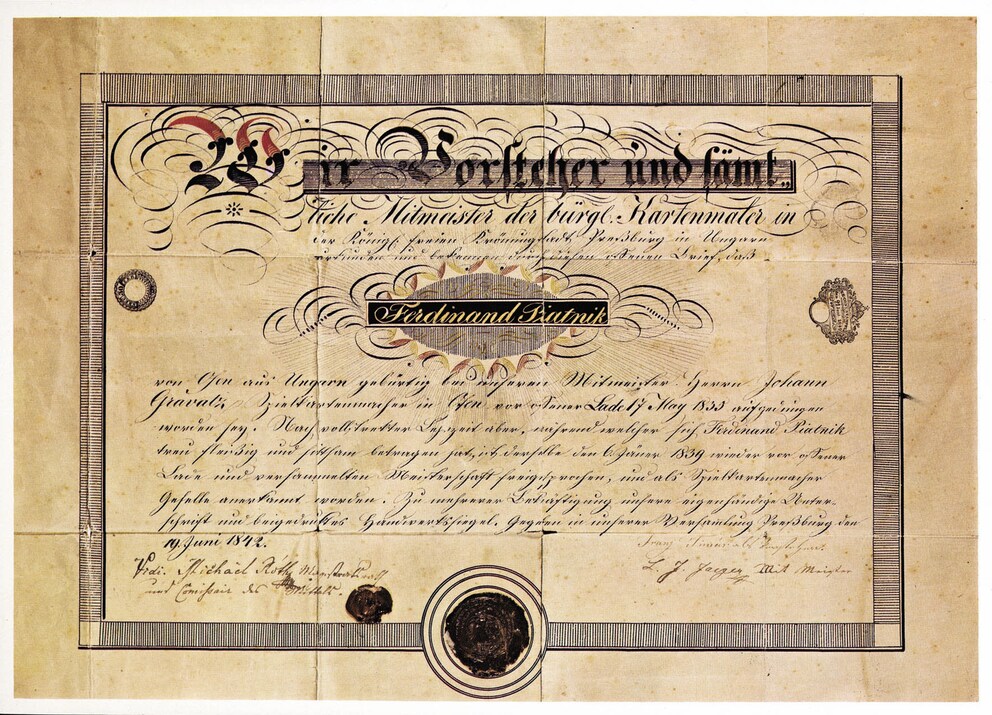

Piatnik was originally a handicraft business. In 1824, Ferdinand Piatnik, a trained card painter, takes over the card painting shop opened by Anton Moser in Vienna’s seventh district. Here, card games are produced by hand until 1891, when the driving forces of new generations and industrialisation increasingly bring machines into the mix. When World War II later decimates the markets in Eastern Europe, the company has to recalibrate. What follows is an expansion into England, Scandinavia and Switzerland. After 1945, the range expands to include board games and later puzzles.

Today, Piatnik is no longer a card painting workshop. Instead, it’s a game manufacturer selling millions of products in 72 countries. Twenty-five new card and board games are released each year, with up to 85 per cent of production facilities located in Vienna and neighbouring EU countries. But what sparked the inspiration for two centuries of gaming fun?

For starters, you need a bright idea from an author or a fellow manufacturer. «Think of it as being like a book publishing house. We also have someone who reads through the manuscript first,» explains Dieter Strehl. One example of where ideas are presented is at game conventions. Most of the time, though, a large group sifts through submissions from authors and tests them several times.

Board game design: the profession that can’t be taught

«You can’t study or train to become a board game designer. In fact, it’s a profession you need a natural talent or affinity for,» says Strehl. It’s a realisation that also dawned on Florian Mayerhofer, who turned his passion for game development into a job: «I find getting into the creative nitty-gritty of a game fulfilling.»

The cabinet behind Florian is full of homemade game prototypes. In front of it, there are piles of handmade boxes containing board games, carefully painted cards and handcrafted game figures. Florian sifts through around a thousand submissions a year from agencies, writers and game enthusiasts. After they get in touch by e-mail, they’re requested to send in a prototype, which goes through a rigorous round of testing with the design team and external testers. About 95 per cent of game ideas are eliminated here, with a negligible proportion making it to the shortlist. A good game has to fulfil two criteria: «It should be as simple and accessible as possible, while also teasing out the desire to play it again,» says the game designer.

From concept to fully fledged game

Once an idea for a game has been found, production begins. Game instructions are written, translations prepared, illustrators commissioned and suitable components purchased. Piatnik itself houses most of the production facilities. Across three floors and four departments, individual components are transformed into finished games, such as DTK, Tick Tack Bumm and Activity – top sellers for the last 30 years.

The first step is the pre-printing process. This is when finished designs are approved for printing, and individual card designs are ordered. On one employee’s computer screen, a picture of a young man and his bike are being retouched into German-style playing cards. Once the designs are approved, the playing cards go to be printed in the next room. The printing machine fills the room, pulling the large sheets through its mighty rollers before depositing them at the other side, complete with the intended design. Cards are then punched out of the larger printed sheet, which gives them their signature rounded corners, before they’re coated with plastic.

Next stop: the game assembly line. Here, the individual parts of the card and board games come together to be packed and sealed into the right box. It’s also the location of the game planning team, which keeps track of the entire process. On average, up to 10,000 games go through the assembly line here daily: «It’s like doing a puzzle – we gather the matching pieces from every department, then allocate them to the right game,» explains one employee. All packaged up, the games are finally sent to the warehouse, where shipping is prepared and coordinated.

Why old-school games are still going strong

The shift towards all things digital is just one of many changes to occur in 200 years of company history. According to Dieter Strehl, the digitalisation of the games industry, with players like PlayStation and Switch, can’t push traditional-style games out of the market. «There’s no need for digital. It’s a distraction. Digital games need a power source and updates, and everyone needs to look at some kind of screen, which disrupts the communicative process that is playing games.» What’s more, hybrid games involving tablets and smartphones have proved to be a flop so far: «People don’t want them. They want analogue games.»

Whether digital or analogue, there’s no secret recipe for the perfect game, says Dieter Strehl. «If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s to be humble and more laid-back. Games that I didn’t believe in at first have gone on to become smash hits.» In 2012, for example, a duo of authors present their idea for a quiz game «Smart 10». The game manufacturer rejects the idea: «Quiz games? Bound to fail, I thought.» When the game is eventually released by a Finnish manufacturer, winning «Game of the Year», Piatnik launches German and Hungarian versions. «Smart 10» wins awards in Germany and Austria, too, and goes on to be adapted into a TV show. It’s broadcast several times a week on Austrian TV.

Photo: Hanna Haböck

Olivia Leimpeters-Leth

Autorin von customize mediahouse

I'm a sucker for flowery turns of phrase and allegorical language. Clever metaphors are my Kryptonite – even if, sometimes, it's better to just get to the point. Everything I write is edited by my cat, which I reckon is more «pet humanisation» than metaphor. When I'm not at my desk, I enjoy going hiking, taking part in fireside jamming sessions, dragging my exhausted body out to do some sport and hitting the occasional party.