Background information

Hands-on test of the Sony Alpha 7 V: the market leader’s back

by Samuel Buchmann

Last week, NASA released a new image from the James Webb Space Telescope. It shows the Cartwheel Galaxy. I wanted to know how such images are created and whether I could conjure up a better picture than the official one simply from the raw data.

The latest image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) had me wondering once again. It shows the so-called Cartwheel Galaxy in a revolutionary level of detail. It’s about 500 million light years away from us. According to NASA researchers, it got its unique shape from a collision with another galaxy. If you want even greater astronomical detail, I highly recommend this article from the New York Times.

However, as a camera nerd, I was interested in other questions: how does the JWST capture these images? What does the raw data look like? How are they developed? And: can I do it too? The answer to my last question in advance: yes, but definitely not as well as NASA.

First, I need to explain roughly how the JWST’s cameras work. That’s right: cameras. Plural. More precisely, they’re called measuring instruments in this case. The JWST uses four types of them. All of them record a different chunk in the field of view of the gigantic, gold-coated mirror module, which sends bundled light to the sensors. For simplicity, I will focus on the two instruments that are relevant to my image: the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

But first things first: all the colours you see in JWST images are fictitious. Both in my picture (on the left) as in NASA’s. The sensors don’t record visible colours, as opposed to your Canon or my Sony at home. Instead, they’re built to see infrared. This «colour» has longer waves than our eye can perceive – and long waves are the only thing that penetrates from far away galaxies to us. A few months ago, my colleague David explained why this is the case in greater detail in an article. In a nutshell: the universe, and thus light waves from distant objects, appear to be expanding. In addition, infrared penetrates cosmic dust better.

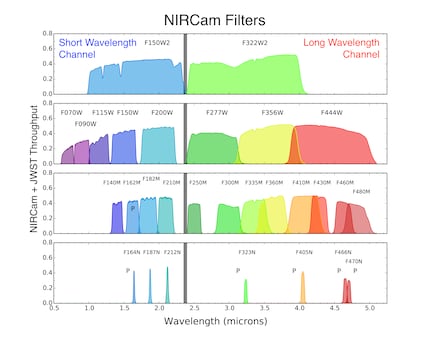

As you can see in the graph, a NIRCam sensor records wavelengths from about 0.6 μm to 5 μm. The abbreviation «μm» stands for micrometer, or one thousandth of a millimetre. Waves of visible red light are up to about 0.7 μm long. The NIRCam doesn’t capture a single image containing all these «colours» combined, as we know it from our cameras. It uses only a monochrome sensor – a black-and-white camera.

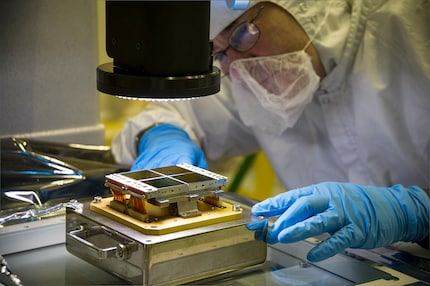

In order to nevertheless distinguish different wavelengths, the NIRCam makes several exposures of the same image section. Each time, a different filter is inserted, which allows only a specific wavelength of light (or infrared colour) to pass through. You can see the mechanics of the MIRI filter wheel in the following video.

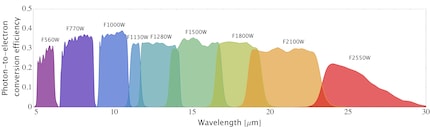

The Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) sensor goes even further. It can record wavelengths from 5 to 28 μm. Revolutionary, as it allows MIRI to stare deeper and in more detail into space than we’ve ever been able to before. For comparison, the Hubble telescope only sees wavelengths down to 2.4 μm. For MIRI’s sensor to work, it must be at least -267° Celsius cold. It’s part of the reason NASA shot it into space, shaded it with a sail, and still has to actively cool it.

If everything goes right, the result from all these sensors and filters is a bunch of black and white images of the same object. This raw data is publicly available on this website, which looks straight out of the 90s. A tutorial on how to filter and download the data can be found here. For my image, I’m narrowing the search by the date it was published: 2 August 2022.

My reward: ten subfolders, labelled with the filter that was in front of the sensor for that particular shot – take f1000w, which only transmits light in the 10 μm range. The folders contain file formats I’ve never seen before. After some research it turns out that they are FITS files, a format for astronomical data that NASA specifically developed in 1981. You need a special program to open them, such as PixInsight, for which 45-day trial licences are available. Or simpler freeware such as the FITS Liberator.

I opened my ten images in PixInsight. A few YouTube tutorials and desperate Google searches later, I successfully exported my TIFFs. Already better. If you’re looking for greater detail on this process or want to copy it, I’ll show you which buttons to press in the following video.

With the ten images in a more normal format, I switch to Photoshop, which is more in my comfort zone. I layered them all on top of each other in a single document. The goal now is to merge all ten layers into a single, colourful image. To do this, I need to make them transparent and colour them at the same time. Again, I explained the details of this in the video below.

Essential when editing: I assign each of the ten monochrome source images its own colour. Which ones those should be is in principle a matter of taste. They’re all fake anyway. I decide to take the sequence from our visible colour spectrum. Consequently, I match the image with the shortest invisible wavelengths – the f090w filter – with a colour possessing the shortest visible wavelengths: purple. This is followed by blue, turquoise, green and so on.

Images from the NIRCam are significantly higher resolution (about 18 megapixels) than those from the MIRI (only about 1 megapixel). In the case of the Cartwheel Galaxy, images taken with filters between 2 and 4 μm appear to have the best ratio of image information to noise. I can get the most out of them. Images from the MIRI have to be scaled up a lot. I also have to massively change the tonal values to see anything at all. Nevertheless, in the end you can see things here that the NIRCam doesn’t show – particularly the 10-μm filter MIRI image I coloured yellow clearly flows into the finished composite.

I’m only half satisfied with my final result. I do like the colours better than NASA’s, though. But in the official image, much greater detail and fewer image artefacts are present – especially around the «spokes» of the galaxy. Among other things, this is because I completely ignored elementary things such as calibration images. My knowledge isn’t sufficient for that, and the effort needed to achieve a clean image would be gigantic for me. Going forward, I’ll leave this to the professionals – but my experiment was an exciting insight into the world of space telescopes.

My fingerprint often changes so drastically that my MacBook doesn't recognise it anymore. The reason? If I'm not clinging to a monitor or camera, I'm probably clinging to a rockface by the tips of my fingers.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all